Police dispersing protesters in El Fasher, Darfur. Image from ﺭﻣﺎﺡ ﺍﺩﻡ ﻫﺎﺷﻢ via Facebook. Video published October 21st, 2021

Sudan is buckling under a wave of protests in response to a military coup that dislodged and dissolved the transitional government. In late October, Abdalla Hamdok, the prime minister appointed by protest leaders two years ago, had been arrested and placed under house arrest by the army. Protestors have spilt onto the streets in response. The protests have spread across Sudan, including the African country’s Darfur region.

In North, South and West Darfur States, El Geneina, Nyala, Zalingei and El Fasher are among the towns that continue to be paralysed by protests, and they have been met with a ferocious response by security forces. Even before the military coup on October 24th, tensions were high in El Fasher, a town in the North Darfur State. Protesters gathering in the marketplace as part of the Marches of the Millions faced a crackdown by police.

The demands varied. Groups of demonstrators supported the Forces for Freedom and Change-the Founding Platform (FCC-FP, which is headed by Darfuri rebel leaders) called for the replacement of the current government by a government of technocrats. Other groups demanded civilian rule. Close to Nabd Al Haya hospital and El Fasher Tower, a Facebook video recorded by an activist on a rooftop showed police (deployed in 4x4 technicals to secure government offices) unleashing a volley of tear gas and firing live ammunition in the air to disperse protestors in the town square. The misuse and abuse of tear gas, as well as the use of live ammunition, has been widespread since protests rocked Sudan in late October.

Government and military officials in El Fasher has stepped up the ante since the coup. Activists have recorded the deployment of an armoured personal carrier and Rapid Security Forces (sitting in 4x4 Toyota pickup trucks), a paramilitary associated with the government, to safeguard government buildings to El Fasher’s same square in preparation for more protests which took place later that day.

On October 30th in Nyala, footage showed unidentified security forces opening fire on protesters marching through the town (the video was re-shared on Twitter by Thomas van Linge). @AbuesissaAmel’s tweet claimed those responsible for the use of live ammunition were the ‘janjaweed’. Whether or not it was the RSF that opened fire in this specific incident remains unverified. Footage of the RSF spreading terror, beating civilians and opening fire on demonstrations in 4x4’s commonly used by the paramilitary, however, has been captured in videos shared on social media by activists across Sudan.

Previous actions also show a pattern of using deadly force against civilians in Nyala by security forces. Located in South Darfur State, Nyala and its surrounding areas have been plagued by banditry and tribal clashes between Arabs and non-Arabs killed at least 36 civilians in the surrounding province. Angered by RSF impunity and attacks and widespread insecurity, sit-ins near military and government buildings have become commonplace and security forces commonly respond with force and arrests.

Arrests have also been reported, with at least 47 arrested at gunpoint in Nyala, Zalingei and Aldi’ein. Those detained were comprised mainly of politicians, government officials, lawyers and professionals. The RSF intelligence branch as well as the Security and General Intelligence services were identified by the Sudanese officials association thread those responsible for cutting communications and internet services in Zalingei. It comes as part of the security forces attempts to weaken the unions and workers on strikes and sit-ins which have paralysed local government throughout 2021 across Darfur. Despite the arrests, protests have continued unabated in the face of the government crackdown across the region.

A Forgotten conflict

The protests rocking the region come against the backdrop of a worsening cycle of instability and violence in the Darfur region. The withdrawal of the UN-African Union peacekeeping mission after thirteen years in December 2020 has left a void that bandits and militias have filled (although civilians in Darfur were often angry with the peacekeepers for failing to protect them). Others have pointed the finger at Khartoum. Some have argued that the country’s political transition after Omar al-Bashir’s removal from power had a destabilising effect, stoking grievances between local elites.

Attacks continue and insecurity remains rampant, a fact that has driven many communities to protest against the failure of local governance to protect civilians from bandits and an unaccountable RSF. “It’s the same war still taking place in Darfur,” said Zahra Omer speaking to Vice News, living in a displacement camp in El Fasher. According to Human Rights Watch, inter-communal violence surged in 2020 while the UN recorded an alarming increase in “inter-communal clashes” in Darfur, with 28 incidents between July and December 2020, an 87 per cent increase compared to 2019. In 2021 atrocities have occurred, echoes of the darkest days of the war in Darfur when ethnic cleansing and atrocities led to the deaths of 300,000 people and displaced 2.4m.

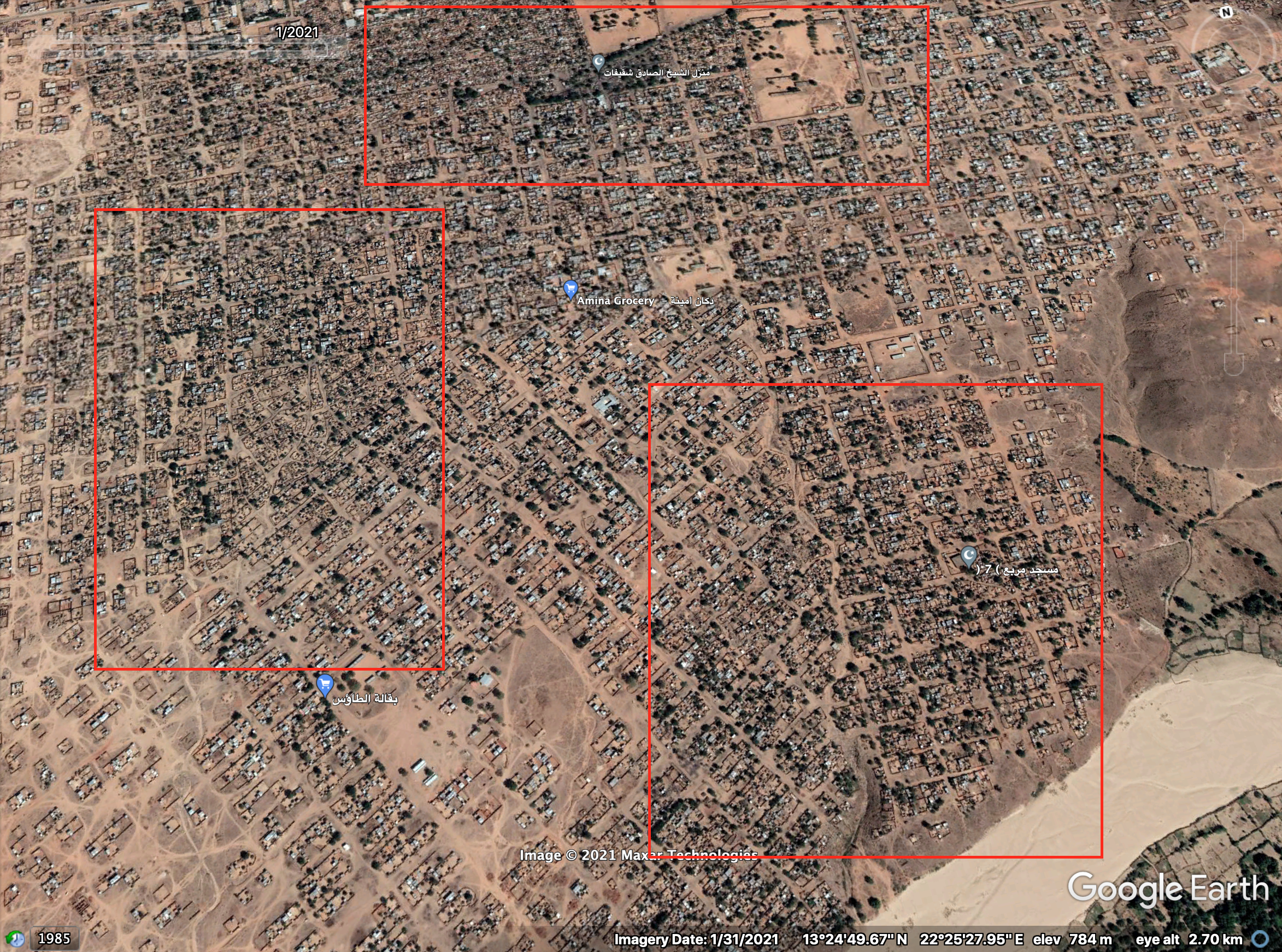

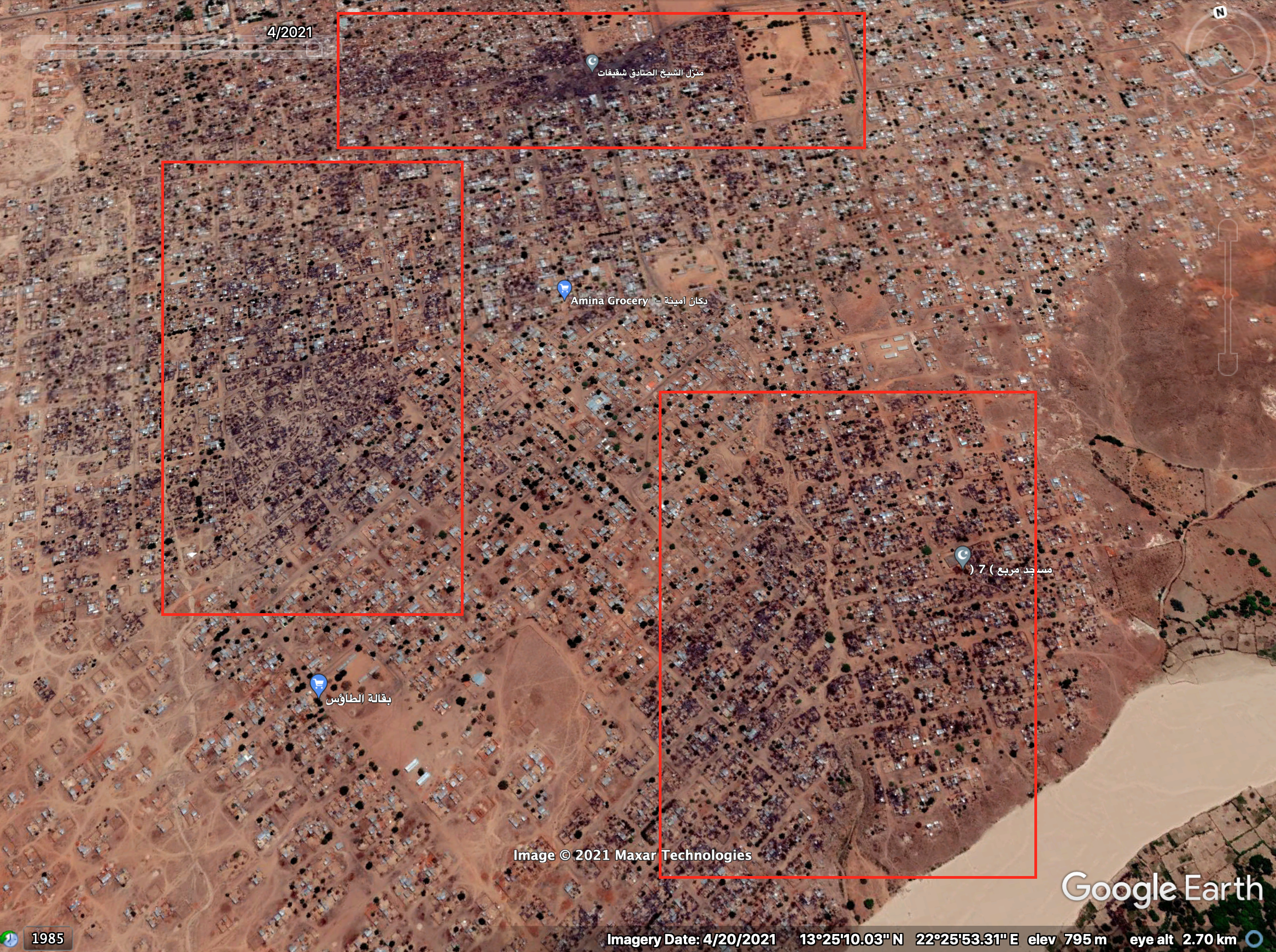

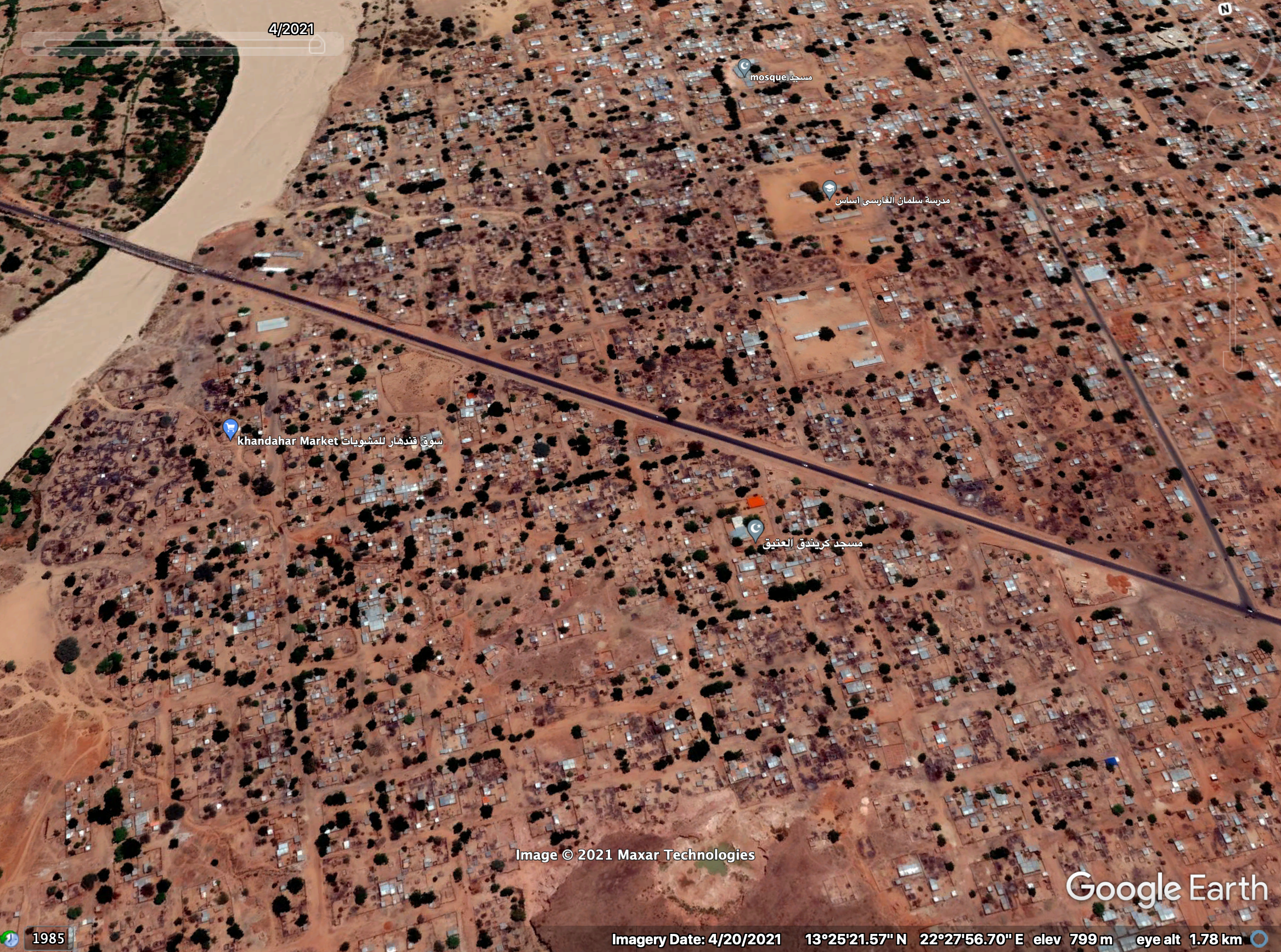

On January 16th in the town of El Geneina, a Massalit tribesman stabbed a member of an “Arab tribe” to death near the Krinding camps to the south-east. Despite the Massalit tribesman being detained, a revenge attack took place escalating into a full-blown assault on the displacement camps. Homes and shops were looted and incinerated with satellite images capturing smoke plumes rising into the skies outside El Geneina. 163 people, mainly from the ethnic Massalit community, were killed with eyewitnesses describing how RSF paramilitaries, supported by men in Chadian military uniforms and militias were involved in the attack. The violence triggered Sudan’s highest number of people displaced by conflict in six years.

January’s slaughter was followed by another explosion of violence in April which killed at least 132 people. In a report published by the African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies, the violence broke out after two Massalit tribesmen were killed on a road separating an Arab residential area and a Massalit one. The Darfur Bar Association described the violence that followed as “amounting to war crimes and crimes against humanity” blaming the security forces for failing to reign in lawless militias and for not investigating the murder of the Massalit men which provoked a revenge attack. The Massalit tribe responded with a retaliatory attack to which the Arabs could not ignore.

Homes were burnt (parts of Abu Zur, a displacement camp in El Geneina were wiped out) and heavy weapons were reportedly used as tens of thousands of civilians fled. The governor of West Darfur blamed the widespread violence on “militias affiliated with the former regime” (the janjaweed who have switched uniforms and become the RSF). Without the presence of peacekeepers, many are terrified to return and for women and girls being displaced, the threat of rape, a favoured instrument of terror during the campaign of ethnic cleansing in 2003 and 2004, remains ever-present.

Before and After: Burnt buildings destroyed by fighting in El Geneina in the west and south of the city. Images via Google Earth.

The worsening violence in Darfur, and now the military coup, coupled with worsening banditry and insecurity has jeopardised the peace agreement agreed in October 2020. The Juba Peace Agreement was paving the way for armed and unarmed opposition groups in Sudan to join the transitional government. Crucially it excluded the two most powerful rebel factions and political divisions remain under the umbrella of rebel groups that signed the agreement. Now that the transitional government no longer exists, it is unclear what happens next in Darfur and beyond.

The janjaweed and bandits are taking advantage of the absence of shutdown telecommunication networks. In Tawilah, 75km to the west of El Fasher, non-Arab farmers are already reporting an increase in attacks by militias on motorbikes and camels. The raiders were described by eyewitnesses as janjaweed allegedly looting, burning and killing and displacing families. The raids in Tawilah displaced at least 2000 families. “The janjaweed did not even leave us our donkeys,” Haja Hussana, a 57-year-old woman who fled with her four children to Zamzam camp. “They took everything from shoes, clothes, and basic necessities for eating and drinking; and they spread terror.” In Shangil Tobayi, an IDP camp also came under attack.

In a region plagued by violence, Darfur’s descent into lawlessness and conflict could have dangerous implications for Sudan. The enduring humanitarian crisis that continues to affect 8.5m people and worsening droughts only add to the toxic mixture as bad politics drives insecurity, instigates ethnic violence and provokes protest. The repressive measures adopted by Sudan’s military junta to disrupt protests against the backdrop of surging violence in the Darfur region could lead to a potential unravelling. Its splintering and a return to all-out conflict would place the region’s forgotten war, and its people’s suffering, firmly back on the international community’s radar. The world turns a blind eye to Darfur’s spiralling cycle of bloodshed at its own risk.