Matthew Williams/The Conflict Archives

Demonstrations have begun in East Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Ramallah. The current U.S administration’s controversial decision to move the American embassy has given life to Palestinian activists and insurgents fighting against the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and its siege of the Gaza Strip, a conflict which has been bubbling beneath the surface for many years. Israeli airstrikes have hit Hamas (Ḥarakat al-Muqāwamah al-ʾIslāmiyyah) leaving two dead and twenty-five wounded while hundreds more have been wounded across the West Bank and Gaza after Hamas called for three "Days of Rage" in response to the decision of President Trump to officially recognise Jerusalem as Israel's capital.

I remember my several visits to the Holy City of Jerusalem in 2016 with much affection when I lived in Israel for four months. Writing on a cafe balcony overlooking the towering white walls catching the late afternoon sunshine with a black Turkish coffee was a treasured moment in my life which I relive over and over in my mind. Jerusalem is a place steeped in history. It was reading the epic opening account by Simon Sebag Montefiore on the siege of Jerusalem in the first Roman-Jewish war which first captured my imagination, I half-expected Jerusalem to be gritty, historical, dusty experience and even uncomfortable in the heat of the day. Quite to the contrary, Jerusalem is extraordinary, modern and it is little wonder why it has been covered by an array of illustrious and tyrannical characters, pilgrims and conquerors throughout its long existence.

Hopping off a tram with a fellow traveller in March 2016, Tom, we arrived just after prayers had finished at the Al-Aqsa mosque. Wave after wave of worshippers poured down the tight El-Wad ha-Gai street locked away from the heat of the sun. Shop owners, young and old, either watched on unperturbed or bellowed out the latest offering and deal for their produce. It was an illustrious array of colours and noise.

The Old City is astonishing in its diversity, the four main quarters being Armenian, Christian, Jewish and Christian. Once the crowds disperse, it becomes very quiet. The imposing, narrow streets become pleasantly quiet you could walk slowly through the streets soaking up the atmosphere. Israeli flags fluttered in the cool breeze, children run about the streets playing, secular and religious people chatted and relaxed in chairs adjacent to their stores or go about their daily chores and groups of tourists occasionally pass on their way to a specific quarter. You immediately knew which quarter you are in by the religious iconography on display whether it the Star of David, the crescent of Islam or the Crucifix. The Christian Quarter in the north-west of the Old City feels like you have suddenly arrived in Venetian street. Small churches line the streets with monks, nuns and Greek Orthodox Christians, Roman Catholics and Evangelicals transcend the Road of Pain (the stretch that Jesus carried his cross before the crucifixion) on the way to the holiest place in all of Christianity, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was a maze of sacred sites, dark aisles, stairways, small chapels and corridors from different building periods marked by centuries of use by different nationalities, groups and faiths. There were places of solace where individuals prayed alone and larger areas where pilgrims gathered and queued to worship (including the dark wooden compound which is the Tomb of Jesus), light candles and reflected on their lives, their conflicts, their hopes and prayed. The Muslim Quarter was an intriguing labyrinth of narrow streets, many of which are covered by roofs and vaults, the likes of which are only found in Cairo, Damascus and Marrakech. The scent of orient wafts through the souks and markets, many men and women dress in traditional Islamic clothing such as the hijab and niqab, but many secular men and women walk the streets wearing smart casual clothing and suits and what is deemed suitably conservative clothing. It is here we stopped for lunch to eat a delicious kebab with an assortment of salads, hummus and meat in a little restaurant we found tucked away in the quarter.

There was a commotion outside, yelling, and laughing as a large crowd gathered outside the restaurant. I stood and went outside and asked what all the commotion was about to a young man in his mid-20s. "Soldiers!" he said, pointing. I looked up the sloping pathway towards the Christian Quarter and saw a group of Israeli security forces jogging in the opposite direction. No sooner had I turned to head back, laughing started up again as another group of Israeli soldiers ran through the district. The response from the surrounding Israeli Arabs and Palestinians was a cascade of hoots and mischievous grins from men, women and children.

The high levels of security across the Muslim and Jewish Quarters were evident. Israeli police were armed for military operations and riots, smoke grenade launchers, heavy rifles, riot helmets, and pistols. Whether or not this surge in security was the norm or a response to the shootings and stabbings which were occurring every week across Israel and the Occupied Territories was difficult to evaluate at the time. However, considering the Old City was the starting point of the bloody Al-Aqsa intifada and extremists and fanatics (both Muslim and Jewish) are constantly attempting to alter the status quo at Al-Aqsa and Temple Mount it is safe to say this high level of security is the norm. Jerusalem remains no stranger to violence and revolt.

Matthew Williams/The Conflict Archives: The Al-Aqsa Mosque, the third holiest site in Islam.

The police officer looked indifferently at me, and told me that was the Al-Aqsa compound was to the right as I walked over a wooden rampart overlooking prayers at the Wailing Wall. Sixteen years earlier on September 28, 2000, to-be Prime Minister, Ariel Sharon and an escort of over 1,000 Israeli police officers visited the Temple Mount complex, site of the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa, the holiest place in the world to Jews and the third holiest site in Islam. After declaring that the compound would remain under perpetual Israeli control, it sparked one of the most violent phases of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the second intifada. Sharon's provocation, the failure of peace talks throughout the 1990s, the continued expansion of Israeli settlements on Palestinian land, Palestinian suicide bombings, and the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin combined to boil over into renewed violence.

The years of stories churned out from the Middle East, Europe and the United States of fanaticism, ignorance, and cruel violence had left me skeptical about religion, a tool often exploited, manipulated and utilised by politicians, terrorists, religious leaders and more to achieve power and influence for relatively unholy causes. However, the sheer power of religious sites such as the Wailing Wall, the Al-Aqsa compound and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the power of such sanctity and devotion is something I had never seen before. There is a captivating historical aura deep within the city, and a penetrating spirituality within the walls of the Old City and Jerusalem. It was a humbling and moving experience and one which I will not forget for a long time. People raise an eyebrow when I speak in glowing terms about Jerusalem, yet despite all the violence and tensions surrounding the Holy City, it remains to this day one of my most beloved in the world whoever it belongs to, no matter which nation or conqueror claims it.

It is the contradictions I always struggled to grasp in Israel and the Palestinian Occupied Territories. During my time with Amnesty International, it was the reality of occupation, the reality of the people who suffer, the people of Atir-Umm al-Hiran and Khan al-Ahmar whose homes have been demolished by Israeli authorities, the South Sudanese and Eritrean refugees and asylum seekers subject to racism, hard-right activists, the exploitation and imprisonment, and the death threats to non-governmental organisations and individuals that became the overt focus.

The Israelis created a modern utopia, but at the expense of entire communities and an entire people; the Palestinians. Dr Ahron Bregman was right in his lectures at Kings College London that the Jewish-only settlements are not going anywhere. The ones seen along Route 1 to Jerusalem are designed precisely to make them difficult to remove from the landscape situated on ridges and steep stratified mounds of earth carved out by diggers. Former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak described Israel as a mansion in the jungle. I disagree with that notion; it is precisely the stark differences and the subtle similarities in language and culture which make this place not only intriguing but an inspiring, cultural melting pot.

So many people seemed to know how to live well in the entwined countries of Israel and Palestine. They live and breath for the moment, there was a community, there was a passion for life brought about by the spirituality of the cities steeped in history, culture and religion, the food, the land and the permanency of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Individuals, families and communities basked in the quiet as the violent conflict simmered unpredictably beneath the surface. It was an infectious, painful and inspiring way to live.

Matthew Williams/The Conflict Archives

The current upheaval and violence, ever-present, sparked by President Trump's decision on Jerusalem has catalysed this underlying violence in the wake of the political move. However, it is merely a catalyst. Working for Amnesty International, it was clear that all was not well within Israel and the Occupied Territories and even before my work as an intern in Tel Aviv, there were warning signs that both countries were in trouble. That it was quiet does not necessarily mean peace.

The Israelis and Palestinians have significantly contributed to the Arab Revolutions. "The Arab spring is withering across the Middle East, but blooming in Israel, where the Joint List, a coalition of Islamists, Arab nationalists and progressive activists, is the third-largest bloc in the Knesset, the Israeli parliament." Furthermore, "Israel is the region’s most robust democracy, with independent institutions, civil rights, the rule of law and an aggressive free press. Its universities produce a stream of technical wizardry while its historians ruthlessly strip away Zionism’s founding myths of statehood."

Israel and the Palestinian Territories remain conflicted. The relative quiet on Israel's home front was violently punctured by Gaza Wars in 2012 and 2014 when the Israeli military launched major operations against Palestinian Islamist groups Hamas and Islamic Jihād following the kidnap and murder of three Israeli teenagers, the mass arrest of Hamas associates and rocket-fire into Israel by the Sunni fundamentalist group. The conflicts left 67 Israelis soldiers and civilians dead and killed thousands of Palestinians and left even more wounded.

After the conclusion of the 2014 Gaza War, violence continued. In October 2014, there were mummers that the third intifada was brewing in Jerusalem. In reality, the third intifada began months ago with the kidnapping of the three Israeli teenagers (June 2014) and the immolation of a young Palestinian boy at the hands of right-wing Israeli extremists both events signalling the beginning of protests and riots in the West Bank and the latest Gaza War between Israel and Hamas. Protests and riots continued in the Shu’fat district after fighting between the IDF and Qassam Brigades subsided. A Palestinian rammed his car into a group of passengers waiting in the light rail station which killed a 3-month old baby and injured several others (22nd October 2014). This was swiftly followed by the shooting of a 14-year-old Palestinian-American in protests two days later and the counter-terrorism unit killed a Palestinian man suspected of attempting before to assassinate a leading agitator for increased Jewish access to the Temple Mount/Al-Aqsa compound.

The state of crisis the Holy City led to repeated closures of the Holy Sites. Another car attack followed (5th November 2014) which left many Israelis injured and one policeman dead, is ‘a direct result of incitement’ by the Palestinian Authority and Hamas. This was hours after renewed clashed occurred at the Holy Sites and the resultant shooting of the driver resulted in more riots across the Old City, Shu’fat and Sheikh Jarrah. On 18th November 2014, four Israelis were killed and eight injured as two men armed with a pistol, knives and axes attacked a West Jerusalem synagogue.

Palestinian activism, attacks and protests were mirrored by a surge in settler-led violence against the Palestinian population. A UN OCHA report comment that ‘the number of settler attacks resulting in Palestinian casualties and property damage increased by 32 per cent in 2011 compared to 2010, and by over 144 per cent compared to 2009.’ Al-Haqa, a human right groups based in Ramallah ‘documented a significant increase in the number of settler attacks and in the severity of violence’ in the Palestinian Occupied Territories. Authorities, according to the report, had largely failed to act on the violence as Yesh Din report published in July 2013 demonstrated. Only 8.5% of the investigations concluded by Samaria & Judea (SJ) District Police were indictments served against suspects who committed acts of violence. This is a small number compared against 90.5% of investigations closed without an indictment being served against Israeli civilians acting violently against Palestinian civilians and property.

A horrific attack in July 2015 occurred where settlers murdered a Palestinian mother and her 18-month-year-old baby in an arson attack in Duma. Meir Ettinger, leader of the settler youths who conducted the attack, whose ideological views and previous arson attacks against churches and mosques were well-known by Shin Bet. The Israeli government condemned Ettinger’s acts as a terror attack, but arguably it was once again the actions of the coalition government that catalysed this savage inter-communal violence. On 29th July, in the days before the terrorist act, Prime Minister Netanyahu had announced that 300 new settlements, following the dispute over territory in Beit El, would be relocated and had advanced plans for about 500 new units in east Jerusalem. This deadly attack was accompanied by the murder of a sixteen-year-old Shira Banki and the wounding of five others at a Gay Pride Parade by an ultra-Orthodox Jew who had been previously imprisoned for a similar attack in 2005. Religious extremism it seemed was a problem plaguing Israeli society, a clear threat to innocent Israeli and Palestinian civilians.

Between September 2015 - June 2016, 38 Israelis were killed, 558 were wounded and 235 Palestinians were killed with nearly 4000 being wounded and a further 7000 or more were incarcerated by Israeli security forces. Israel shelled Gaza multiple times in 2016, and its siege with the Egyptian military of the Gaza Strip has choked resources flowing in and out of the 360 square kilometres of land where rivalries between the Palestinians continues unabated, the Israelis, while physically not present as occupiers since September 2005 have cut it off from the world and pepper it with drone strikes and regularly inhibit humanitarian access.

In August 2016, Israel hit Hamas, Islamic Jihad and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine after a rocket was fired from Gaza which landed between two houses in the Israeli community of Sderot. Artillery shells pounded the area of al-Bureij in central Gaza and Beit Hanoun in the north and the Israeli Airforce hit Gaza over 50 times in response to the rocket being launch. Several Palestinians, including a 17-year-old boy, were reportedly wounded.

To put this into context, the Qassam-1 (3 km), Qassam-2 (9 km), Qassam-3 (10 km) and Katyusha rockets (22 km) are those used by Hamas' military wing Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades and Islamic Jihād. These rockets are usually cut to ribbons by the Israelis advanced air defence systems, the Iron Dome which is part of a system Israel is developing, which will also include the Arrow 2, Arrow 3, Iron Beam, Barak 8 and David's Sling. The Israeli air defence system is not foolproof, Amnesty International detailed how Hamas' rocket fire killed civilians in the Negev including Palestinian Bedouins and Israelis living near Gaza City. Nonetheless, Israel's military might, as the regional superpower in the region, has always dwarfed Hamas' military capabilities and most confrontations between the IDF and Hamas have been one-sided, brutal affairs where the IDF have crushed the group's military wing in military contests. Hamas, while supported by Hizbullah, Qatar and Iran, are nowhere near the level of their patrons militarily. The problem for the Israelis is a political one. Uprooting national and ideological beliefs is not solved purely by bombs, rockets, raids and airstrikes.

Matthew Williams/The Conflict Archives

"In the short space of time, since I last visited Israel, there are many more settlements than I remember. They surround and overlook the Palestinian cities and towns," stated Nino grimly. The sun which had accompanied us through the checkpoint at Bethlehem had faded, tucked behind overcast grey clouds that dimmed the olive-green landscape. The sherut weaved between traffic, skeltering along the road as the city of Hebron came into view. We passed a heavily fortified checkpoint, a tower covered by heavy walls and barbed wire which was perfectly placed to overlook the landscape. An Israeli soldier wearing a balaclava and sunglasses stood by an armored jeep overseeing the traffic as the sherut scooted by. The bus stop nearby for the Israeli settlers was plastered with concrete barriers to protect them from Palestinian militants from ramming them. Two women stood there, one holding the hand of her little girl. When I was talking to Dr Ahron Bregman, in March 2016 he said: "When you go to Israel, go to Tel Aviv, go to Ramallah (it is the Tel Aviv of the West Bank), go to the Golan Heights and go to Hebron." I asked him "Why Hebron?" He responded "Hebron is a microcosm of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the occupation. It is becoming the Berlin of the Cold War, a city divided."

For a city that literally means 'friend' in Hebrew, the city's name has been associated with tragedy and its history is synonymous with the most poisonous elements of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. At the height of the British Mandate in Palestine, sixty-seven men, women and children from the Orthodox Jewish community were massacred by Palestinian Arabs armed with knives, axes and clubs. Houses and synagogues were torched and many became refugees following the onslaught of the Arab mob whipped into a frenzy by rumours that the Jewish people in Palestine were planning to seize Temple Mount. The Shaw Commission, the British investigation into the massacre, described the atrocities in detail:

"About 9 o'clock on the morning of the 24th of August, Arabs in Hebron made a most ferocious attack on the Jewish ghetto and on isolated Jewish houses lying outside the crowded quarters of the town. More than 60 Jews including many women and children “ were murdered and more than 50 were wounded. This savage attack, of which no condemnation could be too severe, was accompanied by wanton destruction and looting. Jewish synagogues were desecrated, a Jewish hospital, which had provided treatment for Arabs, was attacked and ransacked, and only the exceptional personal courage displayed by Mr Cafferata, the one British Police Officer in the town“ prevented the outbreak from developing into a general massacre of the Jews in Hebron."

Decades later on February 25, 1994, at the Cave of the Patriarchs, a physician named Baruch Goldstein entered the mosque and armed with a rifle opened fire on Muslim worshippers killing twenty-nine before being overpowered and battered to death with a fire extinguisher. Mr Goldstein, born and raised in Brooklyn, New York had emigrated to Israel in the 1980s serving in the IDF before joining Kach, a radical ultra-nationalist and right-wing party in Israeli Parliament (The Knesset). After the assassination of its leader, Meir Kahane, in November 1990, Mr Goldstein swore revenge against the Palestinian community and after years of anti-Arab incitement, assaults within the mosque, harassing worshippers, racism against occupied Palestinians and Druze serving within the IDF, actions which were carefully watched by the Shin Bet (Israeli secret police), he finally conducted the vicious terrorist attack. The massacre sparked mass-protests across the West Bank leading to a renewed cycle of violence between the IDF, secular and religious settlers, and the Palestinians. Two months after the Cave of Patriarchs massacre, Hamas conducted their suicide bombings in Afula (April 6) and Hadera (April 13) killing fourteen Israelis and wounding eighty-five.

Matthew Williams/The Conflict Archives: Al-Shuhada Stree, Hebron.

In March 2016, Hebron remained the Wild West. In the space of six days in March, several Palestinians had been shot dead by the IDF and armed police after a series of stabbings, shootings and use of vehicles to crush soldiers and policeman on duty in Kiryat Arba on the outskirts of Hebron, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and Jaffa. The IDF and security forces responded by conducting extrajudicial executions on the spot against the assailants, two of whom were aged only eighteen and seventeen years old.

Since the first and second intifada, the Israeli occupation has cemented itself onto Palestinian territory. At the Israeli checkpoint on the edge of Bethlehem, the security barriers erected by Ariel Sharon in 2004-2005 cut into and loomed over the beautiful landscape. Today, Hebron remains a divided city. Under the Oslo Accords signed by the Palestinian Authority and the government of Yitzhak Rabin, it was partitioned into two zones. The first zone, known as H1, which represents 80 per cent of the city, is home to 120,000 Palestinians and is controlled by the Palestinian Authority. The Jews population is prohibited from entering H1.

The second, H2 remains under Israeli control whose settlers and soldiers occupy the remaining 20 per cent of the city. This area includes the holy sites in the centre and stretches out to the eastern edge of the city, where it connects to Kiryat Arba, a settlement connected to the suburbs. The Jewish settler population, numbering 700 in small, fortified urban settlements, also comprises 30,000 Palestinians and Zone H1 is subdivided into territories that are exclusively Arab and others that are exclusively Jewish. The settlers of Hebron, 1% of the city's population, are a notorious community who regularly attack the Palestinians and Israeli soldiers when the latter attempt to blunt settler aggression and 'price tag' attacks against Arab communities, Micha Kurz from the IDF's Nahal Brigade stating that "What we did mostly protected the Palestinians from Jewish violence in the neighbourhood." from knife attacks and harassment.

In Hebron, Nino and I jumped out of the sherut and the surprise was pleasant for a time. There was not an Israeli soldier insight in the Palestinian district. The streets were buzzing with activity as families and friends milled around in a diverse range of shops selling clothes, food and exotic items. Stalls of food ran along the entire street as wooden and metal carts heaved under the mounds of fruits and vegetables. Cars honked irregularly, squeezed into the tight streets and between the white buildings which were sloping downwards into the valley. Men in suits discussed politics and transactions in the streets while others sat on stools and plastic chairs waiting to do business with potential customers. On occasion, I caught a glimpse of the famous Palestinian kefiyyeh donned by Palestinian youth who covered their faces as they threw stones at IDF soldiers during the first and second intifadas, during the height of the 2014 Gaza War and now. Young women hurried to their next classes and young men and boys zigzagged between the bustling crowd to sell merchandise to passers-by. From where we stood, we were the only people from Europe in the centre of Hebron.

After stopping for lunch for falafel, during which I befriended a kid who passionately supported Barcelona F.C, we began to make our way towards the Old City of Hebron. In the background of the restaurant, a Palestinian news channel covering the latest news and during the frequent breaks a reel of images and videos would follow displaying previous historical confrontations between the IDF and Palestinian protestors which would flash across the screen. The atmosphere was hardly tense, yet it could not be mistaken for peace. The towers surrounding the city were a glaring reminder to the Palestinians of the Israeli presence, nor were the immediate absence of Israeli soldiers a sign that the invisible occupation encouraged by Major General Shlomo Gazit and General Moshe Dayan in 1967 had taken root under the 'Operational Principles for the Administered Territories.'

Nearing H1, the streets began to quieten and the vibrancy of the Palestinian markets began to fade. The Jewish neighbourhood was built above the Palestinian homes in the Old City on the Palestinian Kasbah. The Palestinian residents had constructed nets above them as settlers of the Avraham Avinu residents on the floors above, to protect themselves from the stones, rubbish, glass and alcohol they throw down into the street.

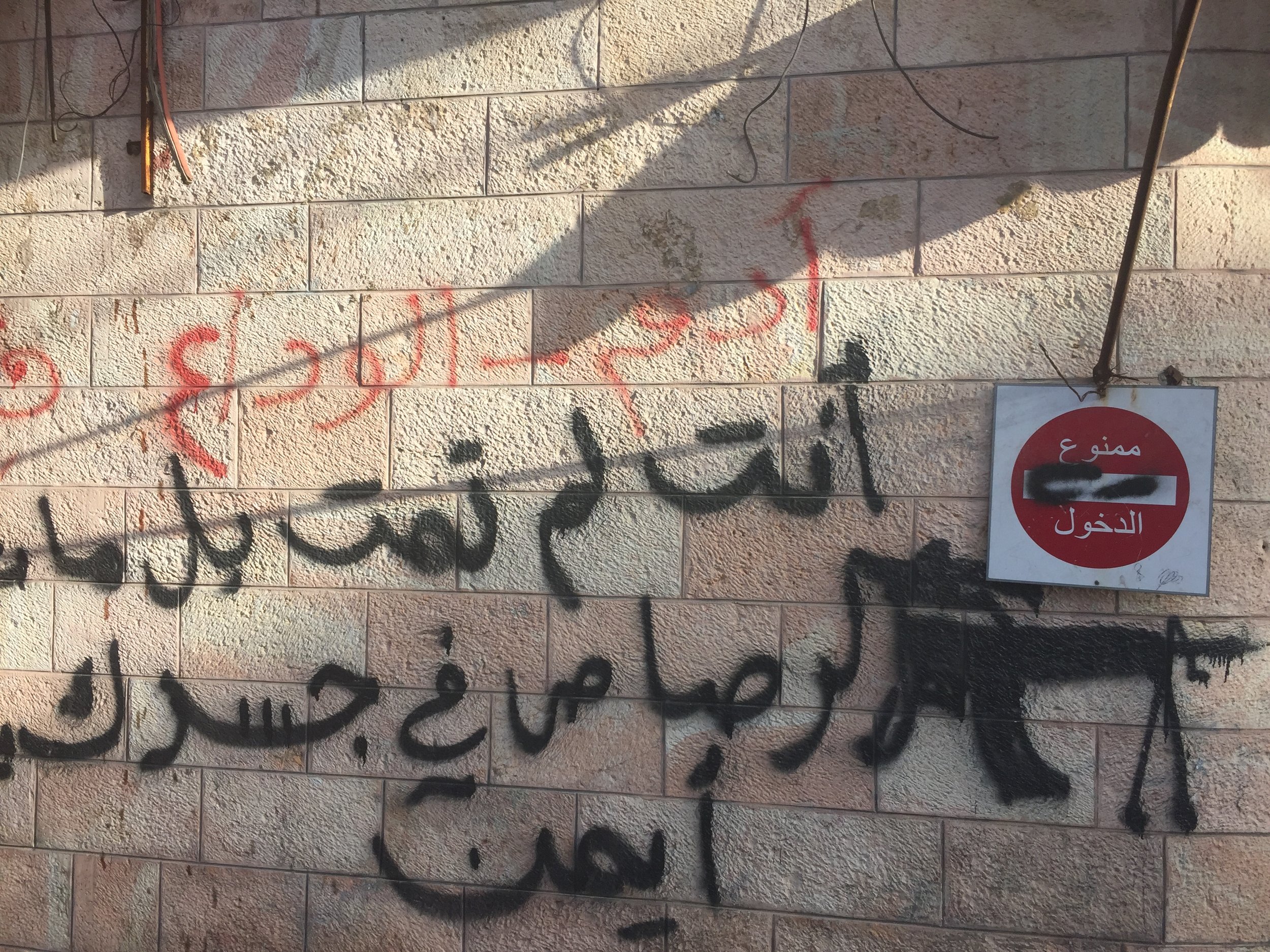

Graffiti sprayed onto the wall in red read "This is Palestine. Fight Ghost Town", a reference to the IDF's closure of Al-Shuhada Street to Palestinians and Arabs. An activist from B'tselem, an Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, briefly took us to the rooftop to show us a better view of parts of the settlement. It was surprisingly derelict and underdeveloped considering its location, and by comparison to the Old City in Jerusalem. Children played in the courtyard of one of the homes. A large graveyard lay on the hillside near a military tower which stood at the dividing point in the road towards Admot Yishai or Tel Rumeida. Eventually, we scanned our passports and entered through the metal gate and went deeper into Avraham Avinu carefully watched by Israeli soldiers. Young Palestinian boys were playing football and men stood at stalls selling Palestinian bracelets and merchandise. The Cave of the Patriarchs stood in the distance where a dozen IDF soldiers sat on the grass as worshippers passed by.

Only Jewish men, women and children walked in the streets surrounding the tomb: Palestinian shops, activity and vehicles had been prohibited from entering Al-Shuhada by the IDF. After visiting the Cave of Patriarchs (during which Israeli policeman ordered him to remove his camera before returning it to him) we walked back along Al-Shuhada Street, the main street leading to the Tomb of the Patriarchs. The glowing sunset looked deeply unsettling as it struggled to break through the subdued sky casting itself in a mournful shadow over the derelict ghost town which had been the Old City. The wide street was empty and slowly greying as if years of unceasing despair had sapped and drained a once vibrant, colourful neighbourhood of life. The cyan-painted rafters were peeling and rusted while the metal doors of the shops of a once-bustling street were an ugly, faded beige as tufts of weed, after months if not years of neglect, growing on the rooftops. The Star of David, Hebrew and Arabic graffiti daubed metal, concrete and wood. The enduring conflict had slowly and excruciatingly exacted a price on the heart of the city.

Tattered Israeli flags flew in the wind as settlers walked by, one serving in the IDF with his rucksack slung over his shoulder as he walked home. One empty building had signs reading "This Land Was Stolen By Arabs Following the Murder of 67 Hebron Jews in 1929. We Demand Justice. Return Our Property to Us: The Jewish Community of Hebron." Further along, a golden sign fitted onto another building read: "Destruction: The 1929 Riots: Arab marauders slaughter Jews. The community is uprooted and destroyed." A worn golden placard to Rabbi Yitzhak Shapira reading "murdered by an Arab terrorist" stood in the archway of one of the building. The history of violence against the Jewish community of Hebron was etched into the minds of the contemporary while slabs of concrete erected to separate Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs added to the pain of this place and the bunker mentality of the Israelis residing in this tiny, tiny district. On route to the military checkpoint at the edge of Tel Rumeida, the exit to the settlement, several IDF soldiers checked our passports before we departed through another maze of metal fences and checkpoint towers dividing the two communities in Hebron.

The day after our departure from Hebron, the execution of Abdel-Fattah al-Sharif by IDF soldier, Elor Azaria following an attack on IDF soldiers on 24 March, 2016 was caught live on camera by B'tselm. Surrounded by soldiers and armed settlers and lying motionless on the ground, Azaria took aim at al-Sharif and shot him through the head. The disturbing footage, while shocking, symbolised the grave situation which grips the Israeli state where soldiers and settlers alike maim with impunity. This was not an isolated incident. The legal, political and moral costs are becoming increasingly stark. Naftali Bennett, newly appointed minister of education and leader of Habayit Hayehudi (The Jewish Home), was quick to defend the soldiers actions:

Avigdor Libermann denounced the criticisms and "onslaught" directed against the Kfir Brigade solider while Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu after originally stating that the incident in Hebron "does not represent the IDF's values," then stated in a Facebook post "The IDF is a moral army that does not execute people...I trust the IDF to perform a thorough, responsible and fair investigation as it always does." In January 2017, Azaria was charged with manslaughter and convicted. However, the conviction cannot ignore the systematic impunity of the occupation and the extra-judicial killings taking place. Since the last Israeli soldier to be convicted of manslaughter in 2005 (Taysir Heib), who was jailed for eight years for killing a British journalist, six thousand Palestinians have been killed.

Onwards to Nablus we drove, past Al-Labban Sharqiya and Jifna where olive trees were encased within grey, scaly brick walls. Many olive groves we had passed previously had been incarcerated by ugly wire fences, meshing together metal with branch, enclosing in and trapping the trees, both protecting and suffocating them from the clutches of settlers. These price tag attacks included acts of arson, the slaughtering of cattle and, on occasion, firebombing Arab homes and violently harassing and shooting farmers in Palestinian lands. Land, this brilliant olive green land, had a blood price on it which smeared and distorted its natural glow as if vandalising a fine drawing on the wall. Twisted metal tied down the tree and whether these iron fences were made by Palestinian or Israeli hands, it was a sad sight to see these stunted trees robbed of their magnanimity, the natural ebb and flow of nature.

Matthew Williams/The Conflict Archives: The city of Nablus, a Palestinian city in the West Bank.

From Ramallah to Nablus we went: both famous cities whose people have rebelled, revolted and fought as activists or insurgents against the Israeli occupation from Moshe Dayan's establishment of the "invisible occupation" to the "break-their-bones" policy of Yitzhak Rabin to the brutalisation of Jenin by Ariel Sharon's bulldozers and tanks. The sherut shot through the hills as we headed north from Hebron to the city of Ramallah. After a night of rest in Ramallah, we continued onto Nablus. Settlements stood out like sore thumbs as we neared the city. Israeli cars entered and left passing through the metal fences to keep Palestinians from entering. This settlement was more sophisticated than the other we had passed earlier, a ramshackle construction only recognisable as an illegal outpost because of the Israeli flag fluttering hanging in the heat of the sun. The security tight settlement loomed above us as we drove by. The Israeli occupation is subtle in places and concentrated in others comprising military checkpoints, concrete barriers, segregated roads and army bases. Military bases, for example, are tucked away just over the hilltops in Nablus.

The Israeli settlers, geographically and psychologically looked down on the Palestinians in Nablus and the parallels between segregationist states in the United States and this particular settlement were very troubling. The normality of the illegal settlements, the sheer impunity with which one could violate international law and how we drifted by it without question, the acceptance of the reality drained you. It wasn't a fight, there was no struggle. I was a humanitarian and a traveller soaking up the frontier of the settlement project in the beautiful sunshine. The sureness and quiet nature of it all was vexing. The countryside surrounding Nablus was exquisite, an assortment of lush green fields blanketed the landscape and, once again, olive trees cast shadows on stony fields which were baking in the heat of the late afternoon sun.

Driving into the city, we went through the outskirts of the city. Nino chatted away to a couple of Palestinian teenagers who had hopped into the sherut. IDF soldiers looked on carefully or simply looked very bored as vehicles passed them at checkpoints and the occasional roundabout where military checkpoints existed. Nablus was a charming city, gleaming in the sunshine with homes and bright white tower blocks creeping up the sloping hills sparsely populated by rock and tree and smaller roads which led out of the city. Mosques and churches co-existed, their spires reaching up into the sky. It was one of the most beautiful places I have been to in the Middle East. If Gaza was the cradle of the intifadas and the future of peace in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Nablus was where the intifadas were born in 1967 in the aftermath of the Six-Day War during the "Battle of the Books" where Moshe Dayan was forced to abandon his 'invisible occupation' after activists and teachers protested against Israeli meddling in the Palestinian education system. Sanctions, curfews and punitive measures were taken to break the back of the protests in late 1967.

We departed Nablus for Bethlehem. At a heavily armed checkpoint, armed policeman boarded our bus checking passports and pointed at the man in front of me and beckoned him to come off the bus. He shouted loudly through the window that he is from Italy. The guards had assumed he was a Palestinian and while he was able to remain on the bus, they thoroughly checked his passport before moving on to the rest of us row by row. The Palestinians and Israeli Arabs, who had all departed the bus to have their passes checked, stood and waited in the dim light of early evening. What was routine for the security forces was eye-opening for those few who ventured outside the Tel Avivan bubble to the Palestinian lands being gobbled up by Israel's settlement projects. Days after my arrival to Israel, an American tourist had been stabbed to death in Jaffa on March 8 while coordinated stabbings had occurred earlier in the day in Jerusalem and the Tel Aviv suburb of Petah Tikva. In June 2016, two Palestinian men burst into Market Brenner cafe in Tel Aviv mowing down four civilians with a submachine gun and wounding seven. The horrific murder of an Israeli-American girl, 13, by Mohammed Tarayreh, 19, in Kiryat Arba (June 2016) in some ways came to epitomise the nature of the violence which has affected Israel and the Palestinian Occupied Territories since the conclusion of the 2014 Gaza War; it is grisly and unpredictable.

Political violence and stabbing attacks are now being accompanied by low-intensity ethno-nationalist violence where 'regular people go beyond racist attitudes and undertake vigilante violence against one another. It can be spontaneous, unorganised, individualised, and therefore harder to anticipate and control.' Whether it be price-tag attacks by extremist settlers or lone-wolves and small groups of young Palestinian militants this violence has been fuelled by rumour, tit-for-tat revenge cycles, disinformation and incitement by political figures in Gaza, the West Bank and the Knesset.

As summarised by Adam LeBor, beyond Tel Aviv, "beyond the Green Line, in the territories captured in 1967, is another, much darker world." There Israeli military and governmental authorities regulate a violent regime over the Palestinians which resembles a mixture of a 20th-century colonial administration, Arabic secret police and the former apartheid regime of South Africa. It is routine "separate roads serve illegal settlements on stolen Arab land..." security forces and some settlers "kill and maim with near impunity, incarcerate Palestinian minors...and diverts Palestinians' water supply to settlement swimming pools while denying them permission to build and humiliates them at checkpoints."

Palestinians and Israelis alike are struggling to come to terms with the harrowing legacy of the Al-Aqsa intifada which cost more than four thousand lives. The subsequent period has been defined by periodic, but brutal wars, between Hamas and IDF in Gaza, protests and bouts of violence have occurred in the West Bank and a brief civil war between Hamas and Fatah. Back in Tel Aviv, it is a different world. It is what I found so fascinating about the Holy Land. It is as if we had reentered the Land of the Wizard of Oz. Young Israelis were everywhere celebrating Purim and an illustrious array of costume-clad men and women, citizens and tourists of Tel Aviv, decorate the street chanting, drinking and smoking the night away, singing and soaking up the pleasures of the city. "Two days in the West Bank is like ten days in Tel Aviv.," said Nino. I did not disagree.

The disorientation of transitioning from an occupation to a holiday city on the Mediterranean coastline was an exhausting, invigorating experience. In cosmopolitan and relatively comfortable Tel Aviv, 'a hedonistic, noisy Mediterranean city, inclined often to look out across the sea towards Europe,' comparable to parts of its northern neighbour Lebanon's capital city Beirut. 'The young and relatively affluent are just as pleasure-seeking and just as capable of protecting themselves against the looming future by ignoring it.'

Israel, for all its rhetoric, has not been isolated from the so-called Arab Spring as the brutal Gaza war in the summer of 2014 demonstrated. After the war between Hamas, Islamic Jihād and the IDF, the rumours of a third intifada (labelled by some as a 'The Knife Intifada' spreading across Israel and the Occupied Territories and the threat of a potential third conflict with Lebanon and the military wing of the political party, Hizbullah, have bubbled beneath the surface since the 2006 Lebanon War and the second intifada. The Syrian War sat on Israel's doorstep and the international community was distracted by the historic developments in Syria and Iraq as the peace process between Israelis and Palestinians completely collapsed. The Palestinians and its main political parties, Fatah, Hamas, and the Palestinian Authority (PA) were divided and under the governance of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel had lurched ever further to the political right. After I left Israel, the cycle of violence continued into 2017. In January, a truck attack in Jerusalem killed 4 off-duty IDF soldiers and wounded 17 more, a British student, Hannah Blazon, was murdered in April on a bus with a kitchen knife and a police officer, Hadas Malka, was stabbed to death in June by Palestinian assailants in Jerusalem.

Protests continue, revolt and tragic violence continue to this day. It is an impossible conflict, however, it is not the only conflict driving violence in the Middle East. Ronny, a former IDF soldier and staff-member at Florentin Hostel had a fair point: "Why are people so obsessed with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict when hundreds of thousands of people, perhaps millions, have died in Afghanistan, South Sudan, Syria and Iraq?" This is a question of merit. Since the Arab Revolutions began in 2011, the persistent headache for seasoned policymakers and politicians in the region- the Arab-Israeli conflict - has ebbed and flowed. By comparison to previous confrontations between the Israelis and the Arabs such the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the Israeli intervention in the bloody Lebanese civil war, or the spectacular victory of Moshe Dayan in the Six-Day War, the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Middle Eastern peace process, once regarded by many as the focal point of the region's problems, is largely side-lined by the turmoil in the Arab Middle East.

Reasons are abundant, mainly immediate concerns to the international community and governments in the Western world which have caused this. The Arab Spring was a historic event; Syria, Libya, Yemen and Iraq are consumed by civil war; Egypt has experienced two military coups and two revolutions; Iran and Saudi Arabia's proxy-war has flared dramatically and relations between the countries have deteriorated; The Turkish government was nearly toppled by a military coup in 2016; Europe and the Middle East have been rocked by Daesh, its terrorist attacks and the rise and fall of its proto-state in Iraq and Syria; Al-Qa'ida sub-cells such as Jabhat Fateh al-Sham have found new strength and purpose in the wake of Osama Bin Laden's death and the question of the nation-state of Kurdistan has gained momentum.

The fall-out of the revolutions has sparked the worst refugee crisis since the Second World War and Western states and Russia have both directly intervened in or covertly fuelled the turmoil in several countries with the support of a plethora of state and non-state actors. Old borders have deteriorated, new sub-states and governments have emerged and collapsed, unprecedented demographic changes are reshaping the social fabric of the region and rebellion and insurgency has been met with brutal counter-revolution all of which have catalysed "one of the most significant socio-religious movements in politics today": militant Salafi jihādism.

The Palestinian Nakba of 1947 has been accompanied by several more Nakba's across the region since the Palestinian refugee crisis began and Jewish-Palestinian Civil War. Geo-political contest across the Arab Middle East has broken regional order as war and insurgency since 1945 has led to the deaths of millions of combatants and civilians (over one million are estimated to have died in the First Persian Gulf War (1980-1988)). The Syrian refugee crisis, a tragedy which has caught the imagination of Europe, precedes several others including the Iraqi refugee crisis (1990 - current), the Kurdish diaspora, and the Palestinian refugee crisis (1947-1948 and 1967 - current). These are historic developments which have advanced rapidly and the wars and politics which have fuelled them are interwoven and deeply complex.

The Arab-Israeli conflict has evolved considerably since the First World War. The Palestinian Nakba in 1947-1948 produced a mass exodus of Palestinian Muslims and Christians from Palestine and Jews from Arab countries (including Syria and Iraq) with over 700,000 - 850,000 on each side being displaced. June 5, 2017, marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Six-Day War, a major conflict between Arab and Israeli which shook regional order, buried a discredited Pan-Arab nationalism and laid the foundations for new confrontations between Israel, the West, and the Islamic world. The occupation of the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, the Egyptian Sinai, East Jerusalem and the West Bank also began in 1967, with only the Sinai being relinquished by Israel in the Camp David Accords of 1978.

The Greater Middle East lies at the heart of the global crisis unfolding. As with Mr Gerard Prunier's assessment of Central Africa, the Arab Revolutions are at the same time both typically "Middle Eastern" and typically un-Middle Eastern as the bloodshed in Central Africa was 'typically "African" and typically un-African. Of-course, the legacy of empire cannot be dismissed when assessing the Middle East: "Boundaries did exist, but not in the European sense. They were linguistic, cultural, military, or commercial, and without the neat delineations so much beloved by Western statesman since the treaties of Westphalia. Colonial European logic wreaked havoc with that delicate cobweb of relationships."

The region's ceaseless instability since the Ottoman Empire's decline in the 19th century, its subsequent collapse in the 20th century and the reshuffling of regional order by the Allies in the First World War have resulted in turmoil for over a century. The formal abolition of the Ottoman Empire at the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (November 1922), the Sykes-Picot Agreement (May 1916) and the Balfour Declaration (November 1917) have carried poisonous resentment, conflicting rhetoric and narratives, long-standing grievances and bloodshed. In the Syrian War, the hatred for Sykes-Picot and its decline has been widely known. Following its establishment of a caliphate in June 2014, Daesh used bulldozers to dismantle the Iraqi-Syrian border in a video titled "The End of Sykes-Picot." However, the dramatic demonstration by Daesh should not overlook that millions despised the agreement of the imperial powers to carve up the region. These events, while important, are not strictly the determining factors in explaining the bloody state countries such as Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Libya and Yemen find themselves.

The post-colonial experience and post-Cold War environment left behind by the United States and the Soviet Union, the rise of globalisation, and the astronomical advancements in technology have created a complex world, one that is complicated and chaotic. The collapse of the Berlin Wall ushered in the United States as the world foremost superpower as the Soviet Union collapsed. In the euphoria of the golden era of unfettered capitalism and globalisation, the geo-political and strategic dominance the United States and Europe held overlooked new challenges and left older grievances unaddressed. In some cases, the Western states had enemies it did not comprehend, old and new, and in a world which rapidly became multipolar.

The Congolese Wars, catalysed by the 1994 Rwandan genocide (and Burundi's second bout of genocidal slaughter after 1972), are a largely forgotten episode which shook the African continent. Described by Gerard Prunier as a continental war, the multiple and overlapping wars in Central Africa were the costliest since the Second World War. One-third of Rwanda's population became refugees. In the wake of the genocidal policies of Hutu Power and the Interahamwe militia which led to 800,000 deaths of Tutsis and moderate Hutus in 100 days, 5.4 million men, women and children were estimated to have perished between 1998 and 2004 as the overlapping wars in Central Africa ripped the region apart.

The Congolese Wars involved seven countries directly and another seven indirectly as the collapse of President Mobutu's corrupt regime in Zaire (the Democratic Republic of Congo) marked the passing of an era and the implosion of the Cold War post-colonial order in Africa. The legacy of European colonialism and imperialism, in-part, laid the groundwork for the horrifying violence. The sheer number of protagonists, militias and proxies drew into the Great War for Central Africa wedded to the heart of Africa's reputation as one the world's resource-rich regions contributed to the region's spiral.

In the Balkans, the Yugoslav Wars and the collapse of communist Yugoslavia can be seen as one long conflict divided into at least nine separate wars, rebellions and uprisings, all which involve parts of the disintegrated Balkan nation between 1990 and 2001. Numerous war crimes were committed in the Yugoslav Wars on all sides including systematic rape, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity were committed by military and paramilitary units. The most notorious incident which encapsulated the ultra-violence of the wars was the mass-murder of 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys by Serbian army units under Ratko Mladić’s command in 1995, the worst single massacre in Europe since the Second World War.

Cities such as Sarajevo, Dubrovnik, Mostar and Bihać were besieged and shelled and NATO eventually launched two aerial bombing campaigns in 1995 and 1999 to "ensure a verifiable stop to all military action and the immediate ending of violence and repression." The intervention divided commentators, factions fighting and the international community with many fiercely criticising NATO's operations in Kosovo and Bosnia while at the other end of the spectrum arguing that humanitarian intervention was required to blunt the aggression of Serb and Yugoslav forces against Kosovo Albanians, Bosniak Muslims and Croats. Serbian civilians and the hundred of thousands who became refugees saw the conflict differently.

Each set of conflicts, of-course, had their own context and historical drivers. The Dayton Accords - which brought stability to the Balkans - are not necessarily a blueprint for stability in the Middle East. The collapse of Zaire was made possible by the Rwandan refugee crisis and the disastrous policies of Mobutu as supposed to being caused by the domino effect of revolutions across Central Africa. Sudan and South Sudan have ripped apart by decades of war.

The violence in each region of the world, the complex (and extended) humanitarian emergencies they generated, and the violence is driven by ethnic, religious, separatist and economic forces are rhyming. The Pax Americana, a prosperous time for Western civilisation, was surrounded by monumental changes, changes which the West believed it was impervious to and more consequentially tried to control in the "New World Order" spearheaded by American leadership. Four hijacked planes, each packed with 9000 gallons of jet fuel, and the deaths of 2749 civilians on September 11, 2001, catalysed the crisis in the Middle East as the "Global War on Terror" and the 9/11 wars were initiated by the United States in response to the atrocities of the Saudi Arabian, Osama Bin Laden. The 9/11 Wars, a term coined by journalist Jason Burke, shattered millions of lives across the globe and the consequences of these conflicts and movements the Bush administration ignited are still unfolding. 9/11 is significant precisely because it did not solve anything.

The conflicts in the region continued unabated and since 9/11, new conflicts began and old ones worsened or reignited. Military historian, Andrew Bacevich argues in his book 'America's War for the Greater Middle East' that the Carter doctrine in 1979, a response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the Iranian revolution, paved the way for decades of U.S military intervention in the Greater Middle East, allowing subsequent administrations to expand it to include many countries in the region in the pre-9/11 era. 9/11 was a tragedy born out of the Western states and the United States' multi-generational involvement in the Middle East. It was a major historical event, yet it was not the definitive event.

As John Jenkins, the former British ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Libya, Iraq, Syria wrote in The NewStatesman, "everything is connected" in the region and the last century of Middle Eastern politics and history, not just current affairs, demonstrate this as detailed by Simms, Axworthy and Milton:

The analogies and comparisons - most notably the Thirty Years War - deserve analysis. Simms, Axworthy and Milton are equally correct in asserting that the Israel-Palestinian conflict and the question of Palestinian statehood is "not an important factor in the present situation in Syria or Iraq, nor has it been among the prime concerns of al-Qa'ida or Islamic State, which have both been much more focused on toppling Arab states" in the Middle East. As the war raged in the Gaza Strip in 2014, John Bew stated: "One fallacy that has been exposed in recent years is that the Israel-Palestine conflict was the main source of the Middle East’s wrongs and a “root cause” of international terrorism...It now looks like a wilful oversimplification from an earlier era." Inevitably, the question of Palestinian statehood will not be solved by ending the Syrian War or pushing Islamic State from Mosul, nor can one conflict - even one as bitter a feud as the one between the Israelis and Palestinians - be the root of every grievance across the region.

To historian Sean McMeekin, author of The Ottoman Endgame, "Iraq has arguably become an even greater geopolitical sore point than Israel/Palestine...owing to the proximity of the Sunni triangle near Baghdad and the Shiite holy cities of Kerbala and Najaf." This has produced a "Sunni-Shiite divide more volatile than anywhere else in the Islamic world." The successive conflicts and inner turmoil in post-Ottoman Iraq have demonstrated "Ottoman Mosul and the other Kurdish (and Turkish) areas of the north were never meant to be yoked together with the predominantly Arab Ottoman vilayers of Baghdad and Basra in the south" of the country.

It is through this lens which the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Israeli-Iranian conflict and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict must be understood. The broader picture of recent global history, including the Middle East, reduces the Israeli and Palestinian violence as the definitive driver in the Middle East, places the multiple conflicts between the Arabs and Israelis in part of the same equation of wars unfolding across the region, and continues to emphasise that it remains a critical part of the battlefield.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict's stark politicisation complicates an already complex, protracted conflict with multiple narratives and versions of history which is difficult to explain and difficult to dissect. The complexity of the issues at hand become clear very quickly. The wall cutting deep into the West Bank and Gaza to some represents protection.

The impact of a decade of suicide bombings on the Israeli mindset cannot be underestimated. 168 suicide attacks were conducted by Hamas, Islamic Jihād and Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade between 1989 and 2007. Such several bombings would inevitably leave a deep scar on any society during a conflict and despite the horrific nature of the suicide bombings in Europe, Manchester, London, Paris, Madrid and Brussels combined have suffered far fewer such atrocities. The utilisation of trucks and cars as weapons in terrorist attacks in Nice and Berlin in 2016 and London in 2017 shocked people in Europe. For an Israeli, the wielding of cars as weapons in Grand Theft Auto style assaults would not have come as surprise as it has become a recurring weapon utilised by many Palestinians since the 2014 Gaza War. The psychological and political consequences of such tactics are profound and while Hamas has ceased using the suicide bomber, the continued firing of rockets into Israeli territory have killed numerous Israeli men, women and children and Palestinian-Bedouins in the Negev.

However, the response of the Israelis in Operation Cast Lead (2008) and Operation Protective Edge combined killed 3368 Palestinians and wounded 16000 more. The Israeli responses to the kidnapping of the teenage settlers were draconian and pushed the conflict into a new phase of extreme violence between the warring parties. It is clear belligerence of the Israeli government under Prime Minister Netanyahu, the Palestinian Authority's incompetence and the slide of Israeli politics and public discourse towards the far-right, the dominance of settler movements and the zealous nature of extremists in the Palestinian and Israeli camps has drastically reduced the prospects of a two-state solution and all but destroyed the Oslo Peace Accords. Since the latest round of violence in Gaza, the process has only sped up with a one-state reality becoming the dangerous state of affairs for the array of factions on the ground.

In regards to U.S policy when it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, American partiality has stood in the way of a fair peace process for decades. Donald Trump’s decision differs from other administrations only because he pursues a policy which nakedly pursues favouring the Israelis. Successive administrations from Harry Truman to Ronald Reagan to Bill Clinton to George W. Bush to Barack Obama have played their part in ensuring partiality has continued undeterred.

In the Trump administration, there are multiple factors at play, including geopolitics including the changing relationships between Israel, the Sunni states and Saudi Arabia. U.S policy under the year-old administration has been bullish, unabashedly anti-Iranian and has taken, at-least within the White House itself, a hardline pro-Israeli and pro-Saudi Arabian stance rhetorically. The personality of President Trump himself will only fuel anger, which has seen regular Islamophobia being spouted, the taunting disabled people, the flaunting of xenophobia and displaying misogyny at many turns. He is a friend to neither Israelis nor Palestinians.

Jared Kushner, the president’s son-in-law, the man to lead the Middle Eastern peace process, according to Newsweek, 'failed to disclose his role as a co-director of the Charles and Seryl Kushner Foundation from 2006 to 2015, a time when the group funded an Israeli settlement' which are illegal under international law. The depth to which the peace process had descended has been farcical. Poor decisions, corruption and missed opportunities by the Palestinian leadership have markedly damaged their people's aspirations for a state. Hamas' doctrine is blatantly anti-semitic and does not recognise Israel, and former PA leader, Yasser Arafat, missed several opportunities to get a state during the Oslo peace process and the Camp David Summit, most notably Prime Minister, Ehud Barak's offer to give Arafat "custodianship," though not sovereignty, on the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif).

The IDF is sitting on a boiling pot and the political leadership does not incline to address the question of Palestinian statehood. The Palestinians have nothing to offer and it is against human nature to surrender so much for so little in return. Only a major intifada is likely to move the Israeli and Palestinian leaderships. Donald Trump's move may be what is needed to rejuvenate the peace process is not just the West Bank, but Gaza. As Jean-Pierre Filiu notes:

'To turn back the clock, opening up a more hopeful future, it will be necessary to return to the promising concept that formed part of the Oslo Accords: 'Gaza First'...the siege imposed on Gaza is only reinforcing the grip of the militias and is undermining any viable economic venture...the issues of frontiers and settlements no longer exist in Gaza but it was in Gaza that Israeli-Palestinian relations reached the incandescent stage of extreme violence...Gaza is both the foundation and keystone (where) peace between Israel and Palestine can assume neither meaning nor substance.' (Filiu, Gaza: A History, 340)

In sparking the Jerusalem controversy - a move which to many Palestinians "eliminates" the U.S from the peace process - and being reckless, the Trump administration has brought the Israeli-Palestinian conflict back to the forefront of the Middle Eastern crisis. The National published an article in 2015 stating "Unless there is a dramatic challenge to the status quo, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict will continue to deteriorate with no good end in sight." President Trump just issued a dramatic challenge to that status quo and the Palestinians now have an opportunity to move against the Israeli occupation once more. Prime Minister Netanyahu, President Trump and his supporters, gleeful, will not benefit from this decision in the long-term whether or not it vindicates their decisions and ideological beliefs. The costs of the failures of the political leadership of both sides will be heaped on Palestinians and Israelis during the months and years to come.

This being said, immensely normal lives are led as the permanent shadow of conflict casts a twisted shadow on one of the most beautiful regions in the world. While I did not bear witness to any violence during my time in Israel and the Palestinian Territories, the cycle of violence was never far away, nor the horrific stories. Like any conflict, it is not black or white, the lines of conflict are blurred. Baruch Goldenstein chose vengeance and murder in the Tomb of the Patriarchs after the assassination of his friend and leader, Kahn. Activist Shir Sternberg chose forgiveness and love after the death of one of his close friends in a suicide attack by Hamas. It is these subtle little choices that create the complex grey zone of conflict which is painted so black and white by many modern media outlets, social media timelines and activists on both sides, within and outside the country.

Who can forget visiting a Palestinian home previously burnt to the ground by extremist settlers or the Palestinian teenager "escorted" off a bus for refusing to show his pass (a scene bearing a depressing resemblance to the worst of segregationist America), the stories of stabbings, beatings and shootings in Tel Aviv, the burnt victims of the first bus bombing since the second intifada, the refugees desperate to avoid deportation, extra-judicial killings by security and military personnel from Jerusalem to Hebron to Tel Aviv, IDF soldiers stabbed, shot and rammed by Palestinian militants, the Palestinian girl consigned to a wheelchair after being paralysed by IDF soldiers, the death threats against activists, NGOs and dissidents, the fatal stabbing of the 13-year-old Israeli girl in the West Bank, and the death of two children by aerial bombardment in Gaza? The cumulative effect of this largely crude violence and intolerance is toxic, not to mention how the low-level and increasingly vicious societal violence has normalised.

The sharp increase in the number of settlements in the West Bank and the permanent presence of military bases overlooking Palestinian towns and cities such as Nablus, Ramallah, and divided cities such as Hebron are a stark reminder of the status quo. The question is whether such a status quo is sustainable despite many Israelis and Palestinian elites benefiting from the occupation. The occupation as a writer and former IDF soldier Assaf Gavron notes in his commentary on the recent developments in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the country is "in a fast and alarming downward swirl into a savage, unrepairable society: the occupation is destroying (Israeli) society."

Consumed by political uncertainty, the IDF had its boot firmly on the throat of the Palestinians in the Occupied Territories. The wars to come in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the wider Arab-Israeli conflict will be as consequential as they are blood-soaked and the fragile coalition government under Prime Minister Netanyahu is playing with fire by tapping into nationalist and identity-based rhetoric and stoking ethno-nationalist and religious hatred and prejudice for short-term political support and power.

When these factors are wedded to increasingly racist and discriminatory policies of the government against African refugees and asylum seekers, Israeli Arabs and Palestinians and the perseverance of using increasingly cruel military tactics and rhetoric against its enemies, it paints a bleak future for innocent Israeli and Palestinian men, women and children and the wider stability of a region already in turmoil. The towering walls that segregate societies, the checkpoints, the surge in settlements and military bases around Palestinian cities and towns and retaliatory attacks indicate multiple societies and communities in Israel sliding towards renewed and brutal conflict. While everything appeared quiet on the surface, it is clear the Israeli-Palestinian conflict - indeed the Arab-Israeli conflict - is still a jagged, divisive issue in the Middle East's current crisis.